Climate Modeling

Using climate modeling, researchers gain real-time insights into the past, present, and future impacts of climate change on our planet. Running and analyzing climate models under different greenhouse gas emission scenarios can help guide global economic and political decision makers. Irina Marinov, an associate professor in Penn’s School of Arts & Sciences’ Department of Earth and Environmental Science, explains how climate modeling works, the information these models provide, the challenges of climate modeling, and how she hopes resulting data can be used to improve lives.

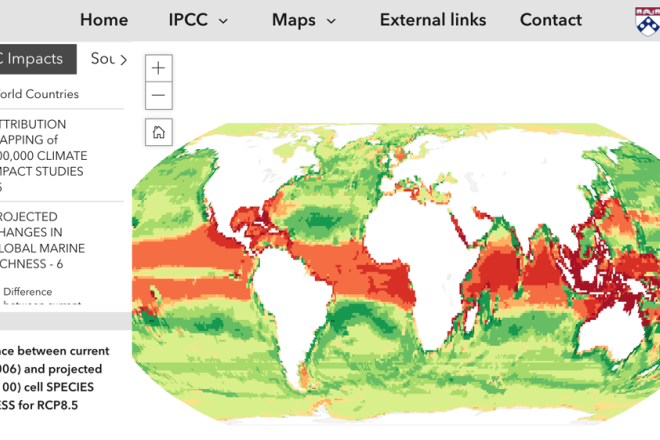

(Description of image at right may be found at the end of this article.)

By Stuti Mankodi

Q: What is climate modeling and how does it help the world?

Marinov: Climate modeling is a way to create a virtual version of Earth using computer simulations. We use complex math, physics, and chemistry to understand how the climate works and how it might change in the future. These models are crucial for predicting things like rising temperatures, sea-level rise, and extreme weather patterns.

For example, climate models help us figure out which regions are most vulnerable to climate impacts, such as droughts or floods. They also assist policymakers in planning for the future, whether it’s building defenses against sea-level rise or deciding how to reduce emissions. Climate models let us compare the costs of acting today versus delaying action. Research with these models shows us why we need to act now and transition to renewable energy fast instead of waiting.

The most recent information coming out of the climate modeling and observational communities is summarized every few years in the UN IPCC Reports (see Glossary). If you want to learn about climate change impacts in your particular region, the latest information is summarized in the U.S. National Climate Assessment 2023 report.

Contemporary climate models are run on supercomputers like the NCAR (National Center for Atmospheric Research) cluster. Penn students work remotely on this supercomputer and analyze model output as part of Marinov’s new “Climate and Big Data” class.

Q: How do climate models work?

Marinov: Climate models start by using well-known equations from classical physics (called the Navier Stokes equations) to describe how energy, water, and greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide interact in the ocean, atmosphere, and land. We compare the output from the models with data from today’s world—things like temperatures, greenhouse gas levels, and satellite-observed chlorophyll —to make sure the model represents today’s reality.

Once the model is set up and verified, we make assumptions about future economic outcomes and run simulations to predict the comprehensive future climate. For instance, we can explore what happens if we reduce carbon emissions or continue our current emission pathway. (We call this latter case the “business as usual” scenario.) We can also ask “what if” questions, like what the climate would look like if we doubled the number of trees on Earth or moved all the mountains from North America to South America. These experiments help us understand how different factors influence the climate.

Q: Is climate prediction similar to weather forecasting?

Marinov: They’re connected but serve different purposes. Weather forecasting looks at short-term changes, like whether it will rain tomorrow or snow next week. It focuses on specific locations and incorporates (in our language “assimilates”) real-time data from satellites and weather stations.

Climate prediction, on the other hand, focuses on long-term trends over decades or centuries. Instead of asking if you’ll need an umbrella tomorrow, climate models answer questions like, “How much will sea levels rise by 2100?” and “Will the East Coast get wetter or drier in the next 30 years?” The basic equations underlying the two types of models (in our language: “the dynamic core” of the models) are the same. But while forecasters use these models for short timeframes (say, one week) and specific locations, climate predictions use them to analyze broader geographical areas over long time periods.

Q: Can climate models predict extreme events like hurricanes or droughts?

Marinov: Climate models are good at capturing large-scale patterns, like predicting which regions will get drier or hotter. For example, they predict that dry subtropics will get drier, while wet high latitudes will get wetter. We can analyze long-term trends in heatwaves or spatial patterns in sea-level rise.

However, because of their low spatial resolution and because they do not constantly incorporate real data, climate models are not meant to predict localized events, like specific hurricanes or urban heatwaves. In general, to model small-scale phenomena, we need higher-resolution models, which require much more computing power, or regional, rather than global, climate models.

Q: What challenges do scientists face when building climate models?

Marinov: One of the biggest challenges is the lack of observations. We’ve only had access to reliable global data for a short time—satellite observations, for example, began in earnest in the 1980s. The oceans are even harder to observe than the atmosphere and building instruments to withstand high enough pressure to monitor the deep ocean is challenging. Remote areas are especially hard to study; the deep ocean is less accessible for ships, as an example, and the polar regions are often covered by clouds, making satellite observations difficult.

Another challenge is computational power. Running complex, high-resolution climate models for hundreds of years takes enormous resources, hence only large labs and institutions typically do it. It can also be difficult to incorporate into models complex processes that occur at small scales, such as cloud formation or small-scale ocean eddies. The interaction of large ice sheets—Greenland and Antarctica, notably—with the climate system is another research frontier that climate scientists are working to better understand.

A critical part of this process is collecting reliable data, and that’s where tools like Argo floats come in. Argo floats are autonomous, battery-powered devices that drift through the ocean to measure variables like temperature, salinity, nutrients, oxygen and pH. These floats dive to 2,000 meters or deeper underwater, collect data while moving with the currents, and then surface to send the information to satellites. They repeat this cycle every few days for up to five years. The data they provide is freely available online, updated daily, and invaluable for improving our understanding of the ocean’s role in climate systems. Argo floats help us observe unusual changes in ocean temperatures, which can influence extreme weather patterns and long-term climate trends. They also help us understand ocean acidification and anoxia patterns. They can provide physical and biogeochemical information from places where research vessels have no chance to go, such as in wintertime and under ice in the Southern Ocean.

Penn students analyze basic ocean variables observed from Argo floats. To find out the status of the global floats today and download data, go to: https://argo.ucsd.edu/about/status/

Q: The oceans are a special focus of your research. Can you explain why oceans are so important for the climate?

Marinov: Oceans cover 70% of the Earth’s surface and play a massive role in regulating the climate. They absorb more than 90% of the extra heat caused by greenhouse gases and take up more than a quarter of the carbon dioxide we emit each year. Without the oceans, our planet would be much hotter.

Because the oceans store heat and carbon for so long, even if we stopped emitting carbon dioxide today, global warming would continue for a while, because the oceans would slowly release the heat they’ve absorbed. Oceans also give rise to the water vapor in the atmosphere, driving the global water cycle.

Oceans today face major challenges: ocean warming and the resulting increase in sea level, changes in global currents, and acidification. These changes threaten marine life and coastal communities. Ocean warming can amplify extreme weather events like hurricanes and can directly affect our local climate.

Q: Are climate model results available to the public?

Marinov: Absolutely. Climate science is one of the most transparent fields. Most 21st century predictions from the latest generation climate models (produced by more than 50 governmental and university groups around the world) are freely available online. Satellite datasets and in-situ ocean, land and atmosphere are open to the public on NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) and NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) websites. Many climate modelers also make our codes available on GitHub.

This openness is especially important for researchers who are not part of large climate research groups or are from nations that may lack the resources to create their own models. Sharing this knowledge helps everyone prepare for climate impacts and mitigate climate change.

Q: Where do I go to find climate model output and real data online?

- Researchers and the public can freely access international model outputs, including simulations of various climate scenarios, from the Earth System Grid Federation data node hosted by the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/

- Open source access to climate model projections and climate observations is possible via NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI): https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/

- The Main Data Portal for Accessing global Argo Floats is hosted by the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, and can be found here: https://www.argo.ucsd.edu/

Q: Can you give us some examples of your current work?

Marinov: Work from the Environmental Innovations Initiative Research Community has allowed us to pursue both disciplinary and interdisciplinary work. With involvement from two undergraduate students, we managed to submit a paper on Pacific Ocean ecology and biogeochemistry (Marinov et al., in review). With climate researcher Anna Cabre, a Penn research associate, as well as undergraduate students and Penn philosophy professor Michael Weisberg, we worked on the Global Climate Security Atlas, housed at Perry World House, and published a paper summarizing this new free resource.

With political scientists Erik Wibbels and Jeremy Springman of the Penn Development Research Initiative, we are looking at socio-economic and political impacts of climate change globally. With support from undergraduate researchers, Anna Cabre and I are developing novel interdisciplinary projects for a class I’m teaching this spring, Climate and Big Data. At present, a group of students in my class are analyzing the impact of climate on socioeconomic indicators and migration in Central America. I am experimenting with the idea of classes as climate research incubators or startups which attract students of diverse academic backgrounds, such as from the life and social sciences, policy, or engineering, and shortening their time scale to get into computational, big data climate research.

Q: What inspired you to work on climate modeling?

Marinov: I grew up in Romania and witnessed environmental destruction after the collapse of communist industries. My mother was a hydrologist studying groundwater pollution, so I saw firsthand how these issues affect communities. That inspired me to work on global problems like climate change, which disproportionately impact vulnerable populations and future generations.

For me, climate modeling is not just about science—it’s about equity and ensuring a better future for everyone.

Q: I have heard you mention Science Moms before. What is that?

Marinov: I am proud to be a part of Science Moms, a group of nonpartisan climate scientists who are also moms. We work to demystify climate change and climate solutions, help parents educate themselves and learn how to talk to kids about climate change. Our mission as climate scientists is to protect both our kids’ future and our planet.

Q: We just learned that the recent federal funding situation has affected you personally. Can you share what happened?

Marinov: The Penn EII grant has allowed my group and collaborators Erik Wibbels and Jeremy Springman to apply for and receive a sizable U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) grant for a three-year project focused on the impact of climate on migration. Sadly, our proposal was discontinued earlier this month, only four months after starting, as part of the unexpected cut of the entire MINERVA-DOD program on social science for national security. Additionally, collaborators in the political science department lost multiple grants linked to USAID (U.S. Agency for International Development) funding. Over the past few weeks, friends in climate and ocean sciences have lost jobs at NOAA, NASA, and the National Science Foundation. We fear these cuts at the federal level are just beginning. The sudden defunding directly affects the careers and livelihoods of young and established researchers and support staff, who might now quit climate science careers or development work entirely. These are profound loses for our University, our research fields, and our country as a whole. At a time when the climate is rapidly changing, our country is pulling back from exactly the types of research that can help us adapt and mitigate these changes, and in many cases literally save people’s lives.

All images courtesy of Irina Marinov.

Thanks to Penn EII and Penn Global for support for Climate Security Atlas development.

Image in header:

Penn students have contributed to the Atlas development. Layers so far include climate projections, food & water security, coastal risks, biodiversity, social and political indices environmental risk and footprint indices, geography-infrastructure-population.

IrIna Marinov, PhD, is an associate professor in the University of Pennsylvania Department of Earth and Environmental Science in the School of Arts & Sciences. She is an oceanographer and climate modeler working at the interface of chemical, biological, physical oceanography, and large-scale climate dynamics. She currently works on societal impacts of climate change, with support from the Penn Global Initiative. Marinov is a member of EII’s Internal Advisory Committee, as well as a member of the Penn Faculty Senate Committee on the Institutional Response to the Climate Change (CIRCE).

Learn more

- Irina Marinov’s Ocean and Climate group at Penn, https://web.sas.upenn.edu/oceans-and-climate/

- The Penn Development Research Initiative https://pdri-devlab.upenn.edu/

- The Global Climate Security Atlas at the Perry World House is a tool to visualize and investigate climate problems. This Atlas compiles more than 200 global geophysical datasets and is a project led by Anna Cabre, research associate at in the Department of Earth and Environmental Science and the Department of Physics, Irina Marinov and Michael Weisberg, deputy director of Perry World House, with undergraduate student support: (https://perryworldhouse.upenn.edu/programs-and-reports/projects/global-climate-security-atlas-project/

- https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/ The National Climate Assessment (NCA) assesses the science of climate change and variability and its impacts across the United States (regional breakdown also), now and throughout this century. The NCA was mandated by the Global Change Research Act of. 1990 and has been produced every 4 years or so since.

- The UN IPCC AR6 Climate Change 2021/2022 reports: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/ Report includes: The IPCC WGI: The physical science basis; The IPCC WGII: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; The IPCC WGIII: Mitigation of Climate Change. This is a comprehensive report from the global climate community on the current state of the climate and projected changes.

- Cabré,Kaufmann, I. Marinov and M. Weisberg: Introducing the Global Climate Security Atlas. Global Sustainability. 2024; 7:e25.doi:10.1017/sus.2024.18

- Refining the Global Goal on Adaptation ahead of COP28, Cabre, Fielding, and Weisberg, 2023, International Peace Institute, https://www.ipinst.org/2023/11/refining-the-global-goal-on-adaptation-ahead-of-cop28

- Fifth National Climate Assessment, 2023. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Global Change Research Program.

Glossary

Argo Floats: Argo is an international program that collects oceanic information using free drifting profiling floats. These floats drift with the ocean currents and move up and down between the surface and deep ocean, moving with the currents, and then surface to send the information to satellites. Then every few days they repeat this cycle, and they can do this for up to 5 years.

Climate: Climate is the average weather conditions for a particular location over a long period of time, ranging from months to thousands or millions of years.

Extreme weather: Extreme events are occurrences of unusually severe weather or climate conditions that can cause devastating impacts on communities and agricultural and natural ecosystems. Weather-related extreme events are often short-lived and include heat waves on land or in the oceans, freezes, heavy downpours, tornadoes, tropical cyclones and floods.

Greenhouse gases (GHGs) trap heat in the Earth's atmosphere, contributing to global warming. The most important GHGs are water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide. Increasing GHGs from human activities are driving climate change.

Ocean Acidification: Refers to the process by which the ocean becomes more acidic due to the increased absorption of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere. When CO2 dissolves in seawater, it reacts to form carbonic acid, which lowers the pH of the water. This makes the ocean more acidic, affecting marine life, especially organisms with calcium carbonate shells or skeletons (like corals, shellfish, and plankton). Ocean acidification can disrupt marine ecosystems and fisheries, threatening biodiversity and food security.

Ocean warming: The ocean absorbs most of the excess heat from greenhouse gas emissions, leading to rising ocean temperatures. Increasing ocean temperatures result in sea level rise and changes in ocean circulation and mixing. They affect marine species and ecosystems, causing coral bleaching and the loss of breeding grounds for fish and mammals.

Sea level rise: Sea level rise is an increase in the level of the world’s oceans due to warming of the oceans and melting of land-based ice.

UN IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) Reports: comprehensive assessments published by the IPCC, a body established by the United Nations and the World Meteorological Organization. These reports evaluate the latest scientific knowledge on climate change, its impacts, and potential solutions. They are produced by a large group of scientists and experts from around the world. The IPCC reports are influential in shaping global climate policies and international agreements, such as the Paris Agreement.

Weather: Weather is defined as the state of the atmosphere at a given time and place, with respect to variables such as temperature, moisture, wind speed and direction, and barometric pressure.