Environmental Hazards and Public Health

What do environmental health hazards mean for the health of our communities and what are scientists and health care professionals doing to address them.

By Molly Flanagan

Maintaining good personal health is a complicated puzzle under the best of circumstances: when nutritious diets, safe homes, accessible green spaces, and quality health care are readily available. But what happens when community residents must navigate a harmful environment and social injustices to ensure good health for their families? How can public health experts, health care providers, environmental scientists, and others provide some of those needed missing puzzle pieces?

Many scholars at Penn are hoping to do just that. In the Explainer that follows, hear from two Penn experts, Heather Burris, associate professor of pediatrics at the Perelman School of Medicine, and Marilyn Howarth, an occupational and environmental medicine physician and adjunct associate professor of pharmacology at the Perelman School of Medicine, about what environmental health hazards mean for the health of our communities and what scientists and health care professionals are doing to address them.

A commonly used term when talking about environmental health is “social determinants of health.” Can you define that?

Burris: For a long time, people thought that your health outcomes were due to the genes you inherited from your family. Over time, we have come to recognize that there are several other aspects of modern life that determine our health outcomes. For a while, much of that was considered a result of decision making at an individual level, like diet and exercise choices. These surely have an impact on our health, but in recent decades we have recognized that other contextual factors, like where we live, go to school, and work, along with some other things that we don’t have much control over—for instance, the air we breathe, the water we drink, the plastics or other chemicals that our bodies are exposed to ubiquitously—can also greatly impact our health.

When I think about social determinants of health, it’s really referring to those environmental, contextual factors at play, and there are both negative and positive exposures. On the negative side, we’re thinking about some of those pollutants I mentioned—chemicals and plastics. On the other hand, some positive exposures we might experience in the environment could be shade from trees and proximity to clean water.

Howarth: These social determinants of health are of particular importance in a city like Philadelphia, which has a number of excellent healthcare institutions and yet our population is still not very healthy by many measures, largely because of social determinants of health.

What sorts of health hazards are present in the environment, how does exposure occur, and who is most vulnerable?

Howarth: For some people, their job exposes them to hazards. People with lower incomes are more likely to have jobs that can pose greater risk through more hazardous exposures. For instance, during the peak of COVID-19, those who had direct contact with people, like bus drivers, transit authority workers, and nurses, had much higher risks of infectious disease. Those who work in construction have higher risks for mechanical falls and chemical exposures, such as lead. Every overpass and bridge in this country is painted with lead paint and will continue to be because it’s the most durable. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has regulations for workers to protect themselves, but it’s very common that these regulations aren’t followed well enough to ensure protection, especially considering that there is no such thing as a safe exposure to lead (WHO).

Homes in Philadelphia also represent an important place for exposure. A high percentage, roughly a fifth of our population, lives below the poverty line. People in Philadelphia, more than other cities, tend to own their own homes, partially because of homes being passed down through families and generations from an earlier time when home ownership was much more attainable. Maintenance can be incredibly expensive. In many cases, families don’t have the money to alleviate hazards from water intrusions, pest intrusions, asbestos damage, or peeling lead paint; they are literally making the decision between eating and repairing a roof.

We think of very young children and babies in utero as being the most vulnerable to lead because they are still evolving and developing their nervous systems and brains, but in fact lead can impact people at any age. Lead exposure can interfere with virtually every aspect of brain function, which is why it can cause both cognitive deficits and behavioral problems. In the first two years after birth, children are not only more vulnerable to developing lifelong health impacts but are also more likely to be exposed because they spend a lot of time on the ground and are likely to put their hands in their mouths. It takes one or two paint chips to lead poison a child.

Then there’s air pollution. We now know that air pollution causes premature births, low birth weight in children, and is a significant driver of heart disease and heart attacks. Air pollution exposure is also associated with dementia.

It's important to recognize that environmental exposures are cumulative. We're pretty good at designing studies that look at a population that’s exposed to one chemical, compare outcomes to a population not exposed to that chemical, and then find a difference. What we need to do is study how social determinants of health interact with environmental exposures.

How do social determinants of health and environmental exposure relate to each other?

Burris: I'm not an environmental epidemiologist by training, but an appreciator of the folks who have done that formal training. There's a professor at Drexel, Jane Clougherty, who has spent her life’s work thinking about the interaction of social and physical environmental determinants of health. She’ll break it down into thinking about the fact that when we are psychologically stressed, or socially stressed, we might be more susceptible to physical environmental exposures. The cumulative, lived experiences and exposures that we as individuals and communities have shape our health. We all have various susceptibilities and resilience factors to these exposures. If we have many, many challenges all at once, it can overwhelm the body’s ability to stay healthy.

How do environmental exposures impact community-level health outcomes?

Howarth: Let’s look at the Eastwick community in the southwest corner of Philadelphia. It’s immediately adjacent to both the airport and the Clearview Landfill, which is in the process of being remediated. The Darby and Cobbs Creeks come together right in Eastwick, and it’s the most often flooded area in the city. There is every reason to believe that every time these creeks flood, the water flows over the landfill and moves hazardous materials.

Because Philadelphia is a historically industrial city, with lots of pre-1970s regulation chemicals in our soil, residents are exposed to chemicals when floods occur and these soils move into people’s basements, yards, and first floors.

It is a major environmental justice issue; Eastwick is the lowest point in the city, and the creeks are tidally influenced, bringing in water from much more affluent communities upstream in Montgomery County. Like many affluent suburbs across the country, Montgomery County has not done a great job with stormwater management. As a result, excessive amounts of stormwater ends up in nearby creeks, which increases floodwater volumes in Eastwick. I’d like to see policies statewide that would make every municipality manage their stormwater properly.

Burris: There have been some interesting natural experiments that I find really helpful in thinking about this. With the initiation of E-ZPass automatic tolling in New Jersey and Pennsylvania on the turnpikes, emissions and pollution greatly decreased from diminished starting and stopping of vehicles. (Read more.) A subsequent health outcomes study found that birth outcomes among individuals in surrounding communities had lower rates of low birth weight and preterm birth compared to prior. (Read more.)

Another one of these classic studies is with the Atlanta Olympics in 1996, where efforts were expended to reduce traffic and vehicle congestion in the city center during the Games. Due to traffic controls, air pollution decreased significantly, which minimized hospital utilization rates for children with asthma.

These studies are really interesting and useful, because you can’t randomize people to high and low air pollution—you can’t get the quality of evidence like we do in drug trials with placebo controls. You can use natural experiments to try to get potentially causal relationships between environmental toxicants and outcomes.

Healthcare access is one of the many exposures we have as people living in a developed society and it’s one of the many determinants of health. But it’s not the only one. As we can see through Dr. Clougherty’s work, social and physical environmental exposures are often happening concurrently. In our heavily racialized society, communities of color are disproportionately exposed to environmental toxicants and adverse social exposures. The cumulative impact of things like racial trauma, violence, and unjust industrial zoning rules and traffic patterns—such as in Philadelphia—can all simultaneously result in disproportionate adverse health outcomes, on top of the many systemic barriers to adequate healthcare access.

What kind of regulatory measures might you suggest to lessen the burdens of environmental exposures on public health?

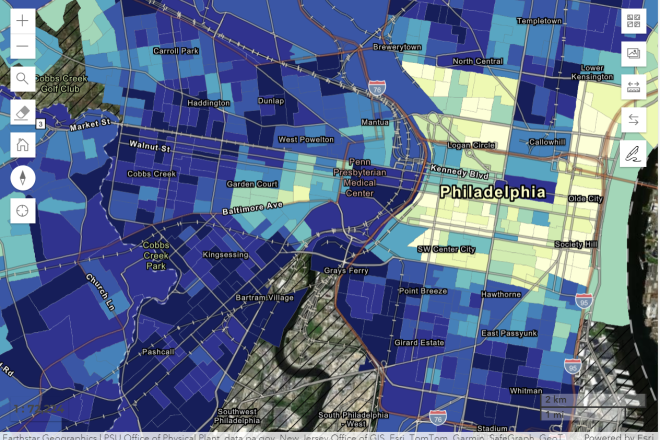

Howarth: The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection has just come out with Penn Enviro Screen. This is a mapping tool that puts environmental exposures as well as and human vulnerabilities—some of the social determinants of health—on the same map with health outcomes like increased asthma rates, heart disease, cancer rates, tracking roughly 30 factors in all. It then identifies census tracts throughout the state that are more vulnerable or overburdened. I believe the state should be able to assign protection factors to decrease pollution permits in some of these areas.

When the EPA makes a new regulation, the first thing that typically happens is that the industry impacted by the regulation files a lawsuit. If the EPA has based its regulation on quantitative metrics, it often can prevail in court. The more quantitative we can make these distinctions between overburdened communities and others, the more likely these kinds of regulations that could stem from mapping tools would likely stand up in court.

Burris: It’s important to do mixed methods studies where you’re getting some kind of quantitative population data, but also dig deeper into families’ experiences to fully understand the key drivers that may be responsible for cause-and-effect relationships. For instance, in Chester, we had proposed a study years ago to look at air pollution exposure and child health outcomes. Chester is a city just south of Philadelphia that is completely overburdened by state-permitted industrial air pollution and is home to a majority Black and low-income population. When speaking to families with young children, some parents said, “We don’t let our kids go outside because we’re worried about them getting shot. So maybe you should worry about that and not so much the air pollution.”

This perspective made us really think about the cumulative impacts that social determinants of health and environmental exposures have and redirected our attention towards indoor sources of air pollution rather than external ones. Houses that are very porous will let outdoor air pollution in, exposing children even if they mostly stay inside.

How does climate change influence these topics?

Burris: As our climate is changing and the world is heating up, one of the calls from an environmental justice perspective is to think about air conditioning as a human right, not just a “nice to have,” similar to the way we think about heating. Air conditioning can serve a dual purpose: filtering the air that’s coming into the home and regulating the temperature.

Howarth: The overburdened will be more overburdened. The EPA doesn’t have a standard for assessing the impact of cumulative exposures to a place, and climate change is likely to increase air pollution because of temperature extremes, both cold and hot.

What are some local initiatives aimed at lessening inequitable health outcomes or burdens from environmental exposures?

Burris: I work with Dr. Eugenia South of the Urban Health Lab at Penn, and we have a project around green space and its potential associations or impacts on cardiovascular diseases and pregnancy. She and her team have shown in prior studies that if there is more greening in city areas, there are many positive impacts on health, such as alleviating burdens of excessive heat, as well as reductions in violence.

I also work with an incredible team of researchers from Penn and CHOP—we are now a site of the National Institute of Health’s (NIH) Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) program. This is a national initiative in which 30,000 pregnant people are enrolling to study the impact of environmental exposures on pregnancy and child health outcomes using questionnaires, geographical analyses, and chemical measurements in samples collected, including placenta, urine, hair, shed teeth, blood, and stool. We were really excited when our site was chosen so that Philadelphia families could choose to include their data to support this big project and truly understand the impact of environmental factors, positive and negative, on child health and development in this city. We are in year one of a seven-year project, and have enrolled about over 500 families. Over 200 babies have been born into the study so far so we are off to a great start!

There are not unlimited financial resources to invest in environmental mitigation strategies. We need to have the data to prioritize which factors are most important to get anything done. We've had great examples of policies that have reduced air pollution, like the Clean Air Act, and there are certain policies that have banned specific plasticizers. The reality is that human beings will coexist with chemicals for the foreseeable future. We need to understand which ones are most important to eliminate or reduce our exposures.

Howarth: I think one of the most hopeful things I’ve heard about is the EPA’s proposed regulations on vehicles. Our region in the Northeast is very impacted by vehicle emissions. We have never been in compliance with the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) for ozone and that’s largely because of the nitrogen oxides (NOXs) emitted by vehicles, in addition to the other chemicals that come together to create ozone in the atmosphere. Vehicle emissions are very impactful to our health, and anything we can do to reduce them would be helpful.

I would like to see better public transit. I’d love to see a high-speed line going right down the middle of the Schuylkill Expressway, with walkovers to parking lots along the way. I think there would be much less vehicle emissions if we really could manage better public transportation.

The other piece I think is really important is maintaining our infrastructure. A lot of times there is debris that ends up in the street, in wastewater, grates, and vents, which creates blockage and causes local flooding. Philadelphia’s combined sewer overflow system, whenever it rains more than an inch, sends raw sewage into many of the waterways in and around the city. The way to decrease stormwater runoff is really in part to increase the greening and decrease impervious surfaces.

Is there anything else you would like to highlight?

Howarth: A lot of my work involves community engagement. I think as we form and design solutions to these big environmental problems, it is critically important to do it with community, because often the community members themselves have the best ideas. Even when we have, perhaps, more technically advanced ideas, incorporating their desires and input can make our technical solutions much more acceptable to people, and implementable in the communities we are focused on. I think that the role of community engagement in all solutions is essential.

Heather H. Burris, MD, MPH is an attending neonatologist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and an Associate Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine. She studies social and environmental factors that contribute to perinatal health inequity. She is multiple PI of the NIH-funded Penn-CHOP ECHO site and PI of a pilot trial (PeliCaN) of maternal postpartum care in the NICU for high-risk patients.

Marilyn Howarth, MD, is adjunct associate professor of pharmacology in the Perelman School of Medicine, director of community outreach and engagement core for the Center for Excellence in Environmental Toxicology, senior fellow for the Center for Public Health Initiatives, and deputy director of the Philadelphia Regional Center for Children’s Environmental Health, among other roles. Howarth has held roles working for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Cooper Hospital before joining the Penn faculty in 1995. Her work has served to investigate and tackle occupational and environmental health challenges.

Learn more

- Clean Water Action (non-profit organization)

- Jane Clougherty, ScD, MSc, Drexel University

- Eastwick: From Recovery to Resilience

- Olympic Games Research Study: Impact of changes in transportation and commuting behaviors during the 1996 Summer Olympic Games in Atlanta on air quality and childhood asthma

- Penn Center of Excellence in Environmental Toxicology

- Philadelphia Horticultural Society Stormwater Solutions

- Philadelphia Regional Center for Children’s Environmental Health

Glossary

- Nitrogen oxides (NOx) are a group of reactive gases that can be emitted from natural processes and human activities and have harmful effects on the environment and human health

- Social determinants of health are the non-medical conditions and factors that influence health, well-being, and quality of life, such as economic stability, education, housing, and transportation.

- Environmental exposure refers to contact with potentially harmful substances in the environment, such as chemicals, biological agents, or physical elements. These substances can be found in the air, water, food, or soil.

- An environmental toxicant is a substance or agent that is harmful to the health of organisms and is either produced by humans or introduced into the environment by human activities, such as pesticides, industrial products, carcinogens like asbestos, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs).

- A research design that combines both quantitative (numerical) and qualitative (descriptive) data collection and analysis within a single study is known as a mixed methods study.