Faculty spotlight: Kathleen Morrison

To launch our faculty spotlight series, we feature a Q&A with Kathleen Morrison, faculty director of the Environmental Innovations Initiative.

By Yueqi Tiffany Luo

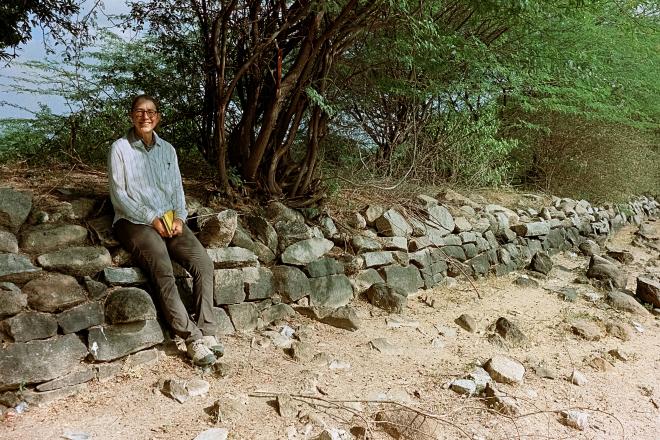

Kathleen Morrison is the Sally and Alvin V. Shoemaker Professor of Anthropology in the School of Arts & Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania, a curator in the Asian Section of the Penn Museum, and faculty lead for the Environmental Innovations Initiative. Her research spans anthropology, archaeology, and paleoecology, involving the study of historic climates and environments, with a focus on South Asia. By connecting the past to the present, her work has implications for the climate crisis, biodiversity loss, and the impact of humans on the environment.

In the Q&A below, Morrison describes some of her most exciting research projects, shares thoughts on biodiversity and climate change, explains why she got involved in the Environmental Innovation Initiative, and offers advice to students interested in a career in the environment.

What are you currently researching that you are excited about?

I’m interested in the long-term effects of human activity on the earth, especially the ways that changing patterns of technology and consumption have led to global-scale changes in land use and climate. But global-scale assessments rely on a lot of smaller-scale research, so I also focus more specifically on South Asia and especially southern India, where my colleagues and students and I use a combination of paleoenvironmental, archaeological, and historical data to understand the last 5,000 years or so of human and natural history. We are especially interested in how farming and other forms of food production have changed, and how those changes affect human societies, landscapes (erosion, hydrology, etc.), and regional biodiversity. I have also worked a lot on irrigation and water, where historical changes turn out to have great contemporary relevance.

I have been working in India since 1985, and it’s taken us that long to really start to track the complex and interconnected histories of humans and the environment – what we call “socionatural histories” – that have transformed the southern Deccan in the Holocene. Building on this work, and the work of hundreds of other scholars across the world, a project I co-direct called LandCover6k is working to aggregate land use and land cover data on a global scale, working directly with climate modelers. That’s very exciting, but also sometimes a slow process. More recently, I’ve started a project with Mark Lycett, Director of Penn’s South Asia Center, at the site of Brahmagiri, in central Karnataka. Here we have the potential to track how both urbanism and deurbanization, as well as changing cultural and political contexts, led to environmental outcomes that differ from places with a long record of irrigation. What seems like ancient history is here highly relevant to the present, from wildlife habitat to rural livelihoods.

How do you see your research contributing to the larger global conversation on climate change and biodiversity?

With the climate crisis and the biodiversity crisis, we’re seeing worsening storms and other disasters, and a loss of thousands of animal species, including pollinators and plant species that are critical to human survival. A lot of my research involves issues of agriculture and the long-term impact of humans on the environment. I study the way people adapt to often very harsh environments and the way they make a living, through farming and animal husbandry. So I have a historical perspective on the changes we are seeing now. In India, we often see that biodiversity conservation tends to displace the very people who are arguably the architects of existing biodiversity hotspots. If we can show how specific kinds of human action actually created and protected biodiversity, then maybe we can help the advocates of forest dwellers and small-scale farmers who are protesting their displacement.

What is your perspective on how we might balance protecting biodiversity while making use of natural resources?

Finding a balance between biodiversity and human use is indeed challenging and has sparked extensive debates. Some argue for intensive agricultural practices on a smaller land area to preserve other land for wildlife and biodiversity. However, this often leads to resource-intensive industrial agriculture, causing negative effects, such as the use of harmful chemicals and the creation of dead zones in water bodies. Scholars studying matrix ecology emphasize the importance of the environmental quality of areas between protected zones, such as agricultural fields and suburban yards. These environments can be improved by reducing or eliminating the use of harmful chemicals, controlling invasive species, and growing native plants. Everyone can contribute to creating friendly habitats for biodiversity, even in small spaces like window boxes and urban and suburban yards. Ultimately, protecting biodiversity requires a multi-faceted approach that includes individual actions, changes in transportation methods, and political engagement.

What courses do you love teaching?

I’m teaching a course this spring called Humans and the Earth System that provides a comprehensive understanding of climate change and its implications across various fields. I team-taught it with two colleagues two years ago for the first time and it was lots of fun. I also teach a course called Agroecology that I really enjoy. I taught it several times in a quarter system, and I’m now adapting it for semesters.

How did you become involved in the Environmental Innovations Initiative at Penn?

About three years ago, I was asked by the Office of the Provost to be one of the faculty directors of the new Environmental Innovations Initiative. This opportunity appealed to me because I am deeply concerned about the current climate crisis and its various aspects. I believe that addressing these crises requires collaboration among different scholars, including engineers, climate scientists, policy experts, urban planners, anthropologists, and more. The Initiative is located in the Office of the Vice Provost for Research and works with all 12 schools at Penn, each with its own perspective, plus dozens of centers. The challenge lies in understanding how these schools and centers work and in bringing together talented individuals from different disciplines to better address environmental crises. The goal is to foster collaboration and find innovative solutions to climate change, biodiversity loss, and other environmental problems.

Are there opportunities for students to get involved with the Initiative's work?

Absolutely. We have been working with graduate student groups like Climate Leaders at Penn and EnviroLab, and the undergraduate group Penn Climate Ventures. Currently, we support research communities that are interdisciplinary and require student involvement. However, we aim to do more for undergraduates and welcome suggestions for their involvement.

What advice do you have for students pursuing a career in the environmental field?

Firstly, I would encourage students to push the university to offer more classes and hire more faculty members in the field of environmental studies. Student pressure can have an impact. In terms of preparing for an environmental career, it is essential to cultivate curiosity, broaden your knowledge, and learn to think in an integrated way. For example, if you are studying urban planning, consider building materials, water flow in urban environments, and the impact of climate change on cities. It is crucial to approach environmental issues from multiple directions and consider solutions that work with people's preferences and needs.

I also encourage students to read widely and spend time in natural places, observing and contemplating the interconnectedness of nature. I understand the struggle of constantly reading the news and feeling overwhelmed. It's important to find a balance. Nature is everywhere, even in urban environments. Pay attention to the plants growing in unexpected places or the interactions between bees and flowers. This kind of observation and contemplation can offer valuable insights and help us develop a deeper awareness of our surroundings. It's also beneficial to take breaks from constant scrolling and instead focus on the world around us.

Are there any books or movies that have inspired you?

I recently read an academic book called Economic Poisoning: Industrial Wastes in the Chemicalization of American Agriculture by Adam Romero. It delves into the history of industrial agriculture in the United States and its connections to urbanization and environmental impacts. I believe books that explain how we arrived at the current situation help us understand the complexity of environmental problems and envision alternative ways to organize the world.