Fast fashion

Cheap and trendy clothing is more accessible than ever, but this convenience comes at a cost to the environment. Two Penn experts, lecturer and alum Jacqui Sadashige of the School of Arts & Sciences and recent grad Sarah Beth Gleeson, co-founder of Baleena, weigh in on the true costs of fast fashion.

By Molly Flanagan

You’re browsing your Instagram feed and come across a chic sweater that will be perfect for keeping cozy this winter. The sweater is linked directly on Instagram Shopping, so there’s no need to switch to another app, and looks just like one from a designer brand that you’ve seen on numerous celebrities. The price seems impossibly low, making the purchase a no-brainer. In fact, you might just add a couple more items to your cart. And voila! You’re able to wear it all the next day—but at what real cost?

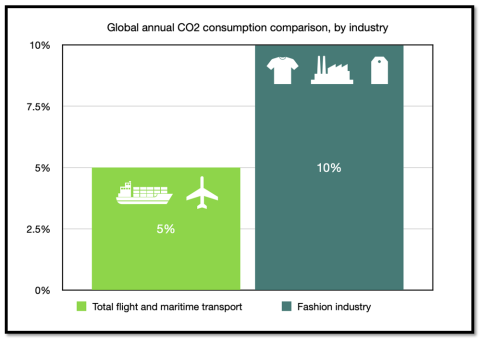

Enter the phenomenon of fast fashion. Today, fashion brands can rapidly manufacture massive amounts of clothing at the lowest and most competitive prices, all while keeping up with the latest trends. Fast fashion has drawn criticism for a number of reasons, not least its harmful effects on the environment. Globally, the industry generates more CO2 emissions than aviation and shipping combined, according to the U.N. Environmental Programme.

It’s a growth industry – in terms of both sales and impact. The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change estimates that emissions from textile manufacturing will increase by 60% before 2030. The low cost of fast fashion is taking a toll on environmental health and welfare, yet the alternative--sustainable or ‘slow’ fashion--often carries a hefty price tag and can be less size-inclusive.

How do these trade-offs come together to advance climate change, and who are most vulnerable to these impacts? We asked two Penn experts, Jacqui Sadashige, a lecturer at the College of Liberal and Professional Studies (LPS), and Sarah Beth Gleeson, Co-Founder and COO of Baleena, a start-up company that developed a device to trap microplastics in laundry and a winner of the 2022 Penn President’s Sustainability Prize, to illuminate the links between fast fashion, environmental degradation, and climate change.

What is fast fashion, and where did it come from?

Sadashige: To a large extent, fast fashion is a business model. Let’s go back through some history. There is a line in the description of the course I teach that says “in 1901, the average American family spent 14% of their annual income on clothing, and by 1929, the average middle class American woman owned a total of nine outfits.” A couple years ago, a company called ClosetMaid found that the average American woman owned about 103 pieces of clothing, so something has changed between the 1920s and now, and part of that has to do with this notion of fast fashion.

In the 1990s moving into the 2000s, low-cost fashion reached a peak. Moving from handmade clothing into industrialization and the development of lower cost fabrics like polyester coincided with an increase in disposable income among the middle class. People had more money to spend on clothing at the same time as clothing prices began dropping, making it possible and desirable for a larger fraction of the public to own more clothing.

If you look at the history of high fashion, like in Paris fashion houses (i.e. Chanel, Louis Vuitton), it used to be that there were only two seasons per year: Fall/Winter and Spring/Summer. If you look at companies like H&M, Zara, Forever 21, etc. they don’t have two seasons. Instead, they may have 52 “micro-seasons.”

The business model that fast fashion is built on is to constantly flood stores or websites with new merchandise. This merchandise is created very quickly and will come in multiple colors, which encourages the buyer to buy various iterations of the same item if they like it, because it’s so easy. If you like one t-shirt, why not buy it in five different colors?

Importantly, it is nearly impossible to copyright fashion. And it is possible, based on companies’ models of production, to see something available for purchase online that was just on the runway at Fashion Week. There is a feedback component utilized by the most efficient companies who know exactly what their customers are buying--how much, and in which locations—so that they can adjust their production process based on consumer demand. Further, with the rise of social media and influencers marketing for brands, there has been a rise in promoting the constant consumption of fashion.

How has the way we value clothing changed over time? How is this reflected in the quality of materials?

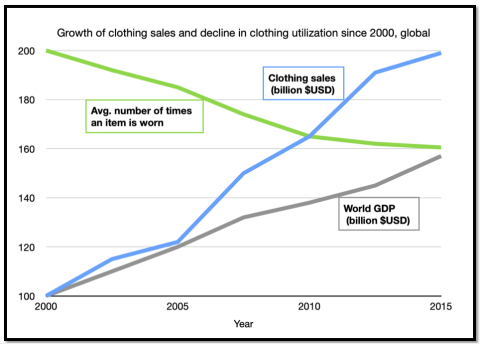

Sadashige: I came across this statistic from Earth.org that says since 2000, clothing sales have doubled annually, while the average number of times an item has been worn decreased by more than 30%. The consumption is going up, the wearing is decreasing, and disposal is increasing.

Gleeson: With the advent of social media, there is this aspect of wearing clothing once and then maybe disposing or getting rid of it. Clothing has just become so readily available that it’s become less about cherishing your clothing and passing it down to, say, your kids, and more about being at the front of the trends. People fix their clothing a lot less often, too, especially when the quality is so low, it’s not even worth it to fix or repair.

To make clothing more accessible and cheaper, the quality of the materials has gone down. Part of that is due to the plastic elements incorporated into clothing, which are relatively cheap; think: synthetic fibers like polyester, nylon, rayon, acrylic and spandex. Around two-thirds of all textiles today are made of plastic or have some plastic component. Plastic fibers shed microplastics, and the lower quality they are, the more they will shed.

How is fast fashion an environmental issue?

Sadashige: I read that the fashion industry is responsible for 10% of total global CO2 emissions, which is as much as the entire European Union (EU) emits.

The fashion industry also uses tremendous amounts of water. If you look at cotton, there was a huge scandal a couple years ago where a bunch of companies thought they were sourcing organic cotton, and that turned out not to be the case. Cotton we think of as being natural, so we imagine it must be a better option, but cotton is actually an incredibly environmentally intensive crop to grow. It uses a massive amount of water, it tends to degrade the land, and requires—if you’re not growing it organically—pesticides and fertilizers. The alternative—synthetic materials—causes microplastic shedding.

Regardless of whether you’re using something that’s organic or a fossil fuel derivative, clothing production requires dyes and other chemical treatments, to stop shrinking, to have garments hold color, or to resist the elements. As you might imagine, if and when these chemicals are released into water systems, they are very toxic to aquatic ecosystems and life.

Recycling textiles is very energy intensive and is not currently done at scale. It’s more expensive to make something out of recycled material, and plastic degrades every time you recycle it. Recycled material also sheds more microplastics, because the fibers themselves are broken down and become shorter and weaker. This is also why recycled polyester almost never produces a garment made of 100% recycled polyester - the fibers are too short after being recycled which results in a drop in quality, necessitating the component of virgin polyester.

Gleeson: Textile waste is frequently sent overseas, often to countries in East Africa and Southeast Asia, sometimes in the name of donations, to rot in landfills hundreds of thousands of miles away rather than be dealt with at ‘home.’

Microplastics are another big issue. They’re dispersed everywhere from our bloodstreams to the Arctic Ocean. From the very inception of a garment’s development to the time we throw a piece of clothing into the wash, it releases microplastics. A single load of laundry releases about 700,000 plastic microfibers, and these fibers are transported into our homes, into wastewater, and into ecosystems. At the ecosystem level, microplastics dispersed in our water enter food chains and are found in the products we eat and the water we drink. Around 94% of U.S. tap water contains some form of microplastics, which contributes to or can cause digestive issues, reproductive health problems, respiratory harm, and other adverse health impacts.

Sarah Beth, your company Baleena aims to trap microplastics during laundering. Can you explain how this technology works and how it might lessen the impact of microplastics in the fashion industry?

Gleeson: At Baleena, we focus primarily on where textiles meet water - this is when microplastics are released from our clothing, and as I mentioned before, it happens a lot throughout an item’s journey, both by consumers when they do a load of laundry, and at the pre-consumer level during textile manufacturing processes like dyeing. After a garment is made, it is run through the laundry a couple times to ensure its performance in the consumer’s washing machine. It turns out that a lot of the microplastics released by clothing are concentrated in the first few washes.

To try and tackle microplastics pollution in the fashion supply chain, Baleena is building next-generation washing machine filtration devices to capture and trap microplastics before they are released into waterways. We are starting at the individual consumer level, but ultimately hoping to move more business-to-business, like textile manufacturers, clothing rental services, laundromats, etc. We’re still at an early stage so we evolve month-to-month.

Who is most vulnerable, or at risk, to the impacts of fast fashion? Why?

Sadashige: As you see with so many global issues, those who are already most vulnerable are going to be those that are at the highest risk. It’s interesting to note that globally, around 60-80% of garment workers are women. If you look at where fast fashion is produced and where these factories are located, they’re in the Global South, by and large. You’re looking at countries like Bangladesh, who suffered the notorious collapse of the Rana Plaza garment factory in 2013, where 1,100 perished, mostly women, employed by Western brands like Zara and Walmart. You’re looking at Indonesia, where there is a high economic dependency on the fashion industry. The workers there are not being paid fair wages and the factories lack oversight.

There is a privilege associated with being able to pay more for a sustainable product. How do we make sustainable clothing more accessible to consumers?

Sadashige: That’s a really challenging question. One of the obvious answers is that corporations must content themselves with making less of a profit, and maybe seeing the profit in lessening their environmental impact.

It’s also the case that all of us have gotten too used to the concept that clothing is disposable. If we got out of that mindset of constantly needing something new - and whether it is that we’re renting or purchasing - then the people who cannot afford to be constantly purchasing new things are not going to feel like there’s this gap.

It sounds like ‘fast fashion’ as a business model cannot become sustainable, but fashion itself can be. What are the barriers in place, and how might we overcome them?

Sadashige: There’s so much happening in that space that is really, really exciting. If we can somehow disentangle this idea that self-expression has to come with some sort of assertion of class, that will help. We shouldn’t be buying into the kind of visibility that says we need to dress a certain way to belong to a certain class or have a certain occupation.

There is also the idea that the burdens of the exploitative fast fashion and fashion industry at large should not be on the consumer. This is where take-back schemes, extended producer responsibility (EPR), and garment repair programs come into play – these programs assign the management of a product’s disposal to the producer. Even a company as large as Coach has a system to take back, configure, and make these unique upcycled bags. Another example is Patagonia, who has established Worn Wear, an online secondhand buying and trading platform for used clothing and gear to extend their lifecycles.

At the same time, consumers do have a lot of power. Rather than viewing this as a consumer problem to solve, consider the tremendous power in collective action.

There are organizations, as well as fabric technology companies, that are doing absolutely fascinating stuff out there. Just like you can grow protein in a lab, you can take that concept to create fibers. I’ve heard about bioengineering a silk that is similar to a spider’s silk but made in a lab. The same chemistry that makes kombucha can also be used to make an alternative to leather. There are also fantastic companies using things like food waste to make new materials and plant-based polymers, or bonding agents, which are biodegradable.

Do you know of any local initiatives helping to combat the rise of fast fashion, or mitigate its impacts on the environment?

Gleeson: There are all sorts of awesome initiatives going on locally. The first is FABSCRAP, a pre-consumer textile recycling service organization that partners with fashion, upholstery, and interior design brands to recycle their textile waste. You can volunteer there most days and take home five free pounds of fabric for your service. Baleena is part of Circular Philadelphia, which has a textile working group. All Together Now PA also has had a textile-related working group, though they are refocusing more on the Fibershed, which is also a really cool initiative to look into.

Sadashige: There are several designers creating fashion from deadstock fabrics in Philly. One is called Grant BLVD and their flagship is right on campus, at 34th and Walnut. Another is called Lobo Mau. There is also The Clothing Closet located in the LGBT Center’s lounge area where students, faculty, staff, and community members may drop off their used, clean clothing or find something to give new life to sustainably.

Jacqui Sadashige

Jacqui Sadashige is a lecturer at Penn’s College of Liberal and Professional Studies (LPS) through Penn’s program in Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies. Jacqui earned her Ph.D. at Penn in classical studies and teaches the Penn LPS Master of Liberal Arts course Fashioning Gender, which explores the ‘far-reaching implications of our love affair with clothes.’ Her course content and expertise has been previously featured in Penn Today.

Sarah Beth Gleeson

Sarah Beth Gleeson is a recent Penn alumna who studied materials science and engineering in the Penn School of Engineering and Applied Science. Sarah Beth is a co-founder and chief operating officer at Baleena, a startup focused on reducing microplastic pollution in waterways. Baleena is working to develop a device to trap microplastics released from clothing and textiles in washing machines, and won the 2022 President's Sustainability Prize at Penn. Baleena was recently featured in the Forbes 30 Under 30 lineup for 2024, in the Energy category.

Learn more

- The environmental and human costs of fast fashion (PBS NewsHour video)

- The Clothing Closet (Penn Today)

- Fashion’s impact in numbers (CNN Style)

- The environmental costs of fast fashion (UNEP)

- America can’t resist fast fashion. Shein, with all its issues, is tailored for it (NPR audio)

- Microplastics found deep in lungs of living people for first time (The Guardian)

- Who, What, Why: Jimil Ataman on the politics and contradictions of slow fashion (Penn Today)

Glossary

Microplastics: extremely small particles of plastic that are less than or equal to 5 millimeters long. These particles can end up in the environment as a result of plastic production, use of plastic products and items, and their disposal (including, but not limited to, synthetic textiles, disposable plastic water bottles, and acrylic nails). Microplastics may be released into the air and water and are essentially found everywhere.

Reference source: NOAA

UN Environment Programme (2019): “In the last four decades, concentrations of these particles appear to have increased significantly in the surface waters of the ocean. Concern about the potential impact of microplastics in the marine environment has gathered momentum during the past few years. The number of scientific investigations has increased, along with public interest and pressure on decision-makers to respond.

Microfiber: a type of synthetic textile made of polyester and nylon; in other words, derived from plastic. It is commonly used in towels, mops, and other cleaning products due to its high level of absorbency and soft, non-abrasive texture. When in contact with water, microfiber products release/shed microplastics.

Reference source: University of Washington

Ecosystem: a term used to define and characterize all of the living (i.e. organisms such as plants, animals, and bacteria) and nonliving entities and processes (i.e. the water cycle, climate, minerals, and soil) in a given geographical area. Ecosystems have great variation around the world, such as in size, age, composition, and level of resilience or change that it can withstand. One common denominator between all ecosystems is that the flow of energy and cycling of nutrients occurs within their bounds, between the living (biotic) and nonliving (abiotic) entities.

Reference source: Britannica

Landfill: a site designated and designed for the disposal of solid waste, such as household garbage. Modern landfills are made up of layers; after a layer of compacted trash is disposed of in the landfill, a cover of soil and plastic seal is placed on top at the end of the day to prevent leaks, odor, and pest interference. Landfills are regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, but can still be dangerous to both human and environmental health. For instance, toxic pollutants can escape the landfill and enter groundwater, air, and surrounding soil which has wide ranging health impacts for local communities. Notably, the location of landfills is disproportionately chosen to be near Black, Brown, and low-income communities in the United States. Landfills also contribute to climate change by releasing greenhouse gasses, like methane, from decomposing waste.

Reference source: National Geographic

Greenwashing: defined by the United Nations as “misleading the public to believe that a company or other entity is doing more to protect the environment than it is.” Greenwashing is often a marketing tactic that may be used to promote unverified claims and solutions to the climate crisis as factual, to reap the benefits of perceived social and environmental responsibility.

Microtrends: refer to very short-lived and viral style, beauty, and other aesthetic-related trends that are popularized on social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram, by celebrities, influencers, and popular culture at large. Microtrends exist outside of the traditional 20-year fashion trend cycle. Some popular microtrends from 2023 include aesthetics like the ultra-pink ‘Barbiecore,’ Succession-popularized ‘Quiet Luxury,’ and ‘Balletcore,’ marked by bows and ballet flats gaining immense commerciality.

Reference source: Vogue

Influencer: refers to an online personality, persona, or individual who uses their platform to inspire actions, such as purchasing goods or services, from their social media followers. Brands and companies utilize influencers in their marketing strategies by offering commissions for referral purchases or outright sponsorships.

Reference sources: Merriam Webster, Cambridge Dictionary

Deadstock: refers to fabric that was made by a textile mill but never utilized in the production of a garment. In other words, deadstock fabric is the unused, surplus fabric leftover from the manufacturing process of a given article of clothing, upholstery, or home textile that is no longer needed for its initial purpose.

Reference source: Good On You

Extended producer responsibility (EPR): EPR is a policy option which requires the producer of a given product to take physical and/or economic and financial responsibility of its product beyond the consumer’s use, extending to disposal and end-of-life. EPR is characterized by a ‘cradle-to-grave' approach and incentivizes producers to prioritize environmental sustainability and waste minimization in the design process of production.

Reference source: OECD