Innovation in climate education

It was 3 a.m. in Philadelphia when Zachary Herrmann, principal investigator of the Project-Based Learning (PBL) for Global Climate Justice Program, kicked off a meeting with 70 educators located in six sites around Asia, Africa, and Europe. Across time zones and continents, they were all gathered with a shared purpose: to increase the likelihood that every K-12 student gets an education that equips them to address real-world challenges, such as climate change and its resulting social inequities.

By Xime Trujillo

It was 3 a.m. in Philadelphia when Zachary Herrmann, principal investigator of the Project-Based Learning (PBL) for Global Climate Justice Program, kicked off a meeting with 70 educators located in six sites around Asia, Africa, and Europe. Across time zones and continents, they were all gathered with a shared purpose: to increase the likelihood that every K-12 student gets an education that equips them to address real-world challenges, such as climate change and its resulting social inequities.

“We knew we were attempting something very different from anything we had attempted before. We honestly weren’t sure what to expect,” confesses Herrmann, adjunct associate professor at Penn’s Graduate School of Education (GSE), describing this inaugural Global Design Sprint. His PBL for Global Climate Justice work has been supported for three years as one of the Environmental Innovations Initiative’s research communities. “We had high hopes for this new professional learning model and what it could mean for scaling our work across the globe,” he says, “and at the end of the day, it exceeded our expectations.”

Together with various Penn colleagues, including GSE’s Taylor Hausburg, Gillian Daar, and Emma Koropp, Herrmann has been exploring the potential of PBL and climate change for three years, developing resources that educators across the globe have leveraged in their own classrooms to create hands-on learning experiences for young students.

Empowered teachers; empowered students

Educators traditionally teach about climate change and its uneven social impacts in ways that can inadvertently disengage students by treating them like passive recipients of information, rather than active agents of change, Herrmann says. Across grades at schools, this content is usually part of a science lecture. But when Penn prioritized climate, underscoring it in its strategic vision In Principle and Practice, Herrmann and the team saw a thrilling opportunity to apply PBL and transform K-12 climate education.

"PBL inspires teachers because it positions their students as active agents who are responding to the climate crises, rather than just learning about it," Herrmann says. Team member Gillian Daar explains, “We are facing so many climate related challenges–it can feel overwhelming. As the educators described their projects, I felt hopeful. Here were over 70 educators from around the world, committed to engaging their students in the world’s most pressing questions and developing projects that had students not just learning about them, but taking action, empowering them to be changemakers in the world.”

“I am grateful for the opportunity to continuously learn about Climate Justice and how I can authentically lead climate initiatives.” - participant, Uganda

A new model for teacher's development

The research community has involved Penn faculty from a variety of disciplinary backgrounds to create content that supports teachers in preparing lessons on climate and extreme heat, weather patterns, and human health. However, Herrmann and colleagues wanted to scale the program up so that teachers could integrate locally relevant content into their lessons while feeling part of a global community. Their solution? A new model of Global Design Sprints.

A Design Sprint is a day-long experience where educators learn the basics of PBL and its applications to help their students grapple with climate issues, and they work together to develop project ideas. During the first two years of the research community, Herrmann and his team facilitated several of these experiences, both in-person and online. Some attendees left the in-person Design Sprints with a lesson idea; others had a significant project they hoped to implement.

“There is a lot of energy and excitement when educators are physically together,” says Hermann, “but it can be costly to replicate and difficult to scale because it requires everyone to be present at a single location.”

In contrast, online Design Sprints have allowed participants from at least 26 countries to learn about PBL and join a growing community of educators. However, the Penn team found the virtual format didn’t elicit the same level of inspiration and commitment from participants. So, they borrowed an idea from NASA Space Apps, a public engagement program where participants worldwide gather at simultaneous in-person and virtual local events to address challenges submitted by experts.

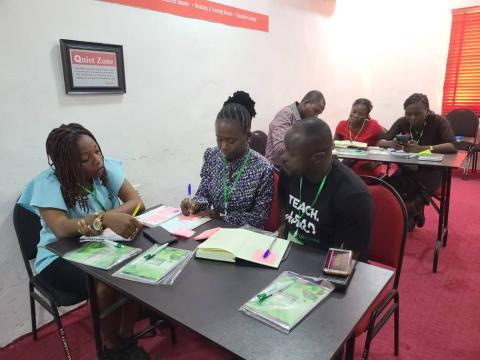

Herrmann and colleagues led the first Global Design Sprint last fall, involving six satellite locations that could engage in-person while accessing real-time opportunities to connect with educators from other sites. Prior to gathering, the research community recruited local hosts through an open application, trained them, and supplied them with guiding materials about PBL and climate change. Then, each site host recruited participants and led their own in-person event, as others did the same in different parts of the world. During the event, Herrmann and his team facilitated exchanges between satellite sites. In their first iteration, the Global Design Sprint connected sites in Nigeria, Uganda, Greece, the Philippines, Taiwan, and China.

Educators in each location applied PBL to locally relevant projects, which ranged in scale and topic. The participants in Greece, for instance, envisioned how young farmers could promote access to local foods to reduce the environmental and climate impact of the food supply chain. Meanwhile, partners in Asia and Africa worked on issues ranging from food scarcity to the fashion industry. For the team’s next Global Design Sprint, planned for March, they expect participation from 10 sites in total.

“More than just a hybrid meeting, this event was a powerful fusion of local and global perspectives...participants joined the global audience to engage in cross-cultural exchanges that redefined their approach to climate issues. This shared experience became a testament to the power of community in addressing global challenges." - Emmanuel Kilasho, site host, Nigeria

One takeaway of the first Global Design Sprint was the importance of the balance between virtual and in-person moderation, and the critical role the local site hosts played in making the experience successful.

Emma Koropp, another team member, explained, “watching the Site Hosts—who we had collaborated with on event preparations for weeks—bring together dozens of educators to exchange ideas, build community, and leave empowered to implement climate-focused projects was incredible. It was a powerful reminder of how much passion exists for this work and how transformative it can be when educators are given the space to support and inspire one another.”

At the same time, teachers appreciated learning from other sites and expressed how beneficial it is to be part of a global community. According to a post-event anonymous survey, 97% of participants indicated they felt connected to a professional network supporting their practice related to PBL climate justice education. In response, Herrmann and the team are looking forward to implementing next steps, conducting follow-ups with satellite hosts and creating a story map to highlight exemplary work from educators around climate change and justice.

“The event offered us a fantastic opportunity to deeply explore the applications of PBL in designing and facilitating student learning in global climate justice… We all left feeling inspired and eager to apply what we've learned to benefit our communities and students.” - Jinsong Li, site host, China

As a research community, for the past three years, Herrmann and the team have drawn together Penn faculty across campus to share their expertise with educators and inform the types of projects that they will implement with their students. As a collective, over 2,400 students may benefit from the takeaways of the first Global Design Sprint.

PBL for Global Climate Justice will continue to grow and innovate in the field of education, supporting educators’ development in a way that is broadly accessible and locally relevant within a global context. The team is inspired to keep growing the program. As research community member Taylor Hausburg reflected, “listening to educators from around the world share their project ideas brought tears to my eyes. They weren't just sharing lesson plans; they were sharing their concerns, hopes, and intentions for the future. It was a beautiful moment of connection—reminding all of us of the why behind our work, validating and celebrating each other's efforts, and feeling part of something larger than ourselves.”