A modern history of ancient trees, through the lens of climate change

By Kristen de Groot

Historian Jared Farmer discusses his new book, ‘Elderflora,’ looking at why humans have no trouble looking at the ancient past but can’t seem to envision the deep future, and what trees can teach us.

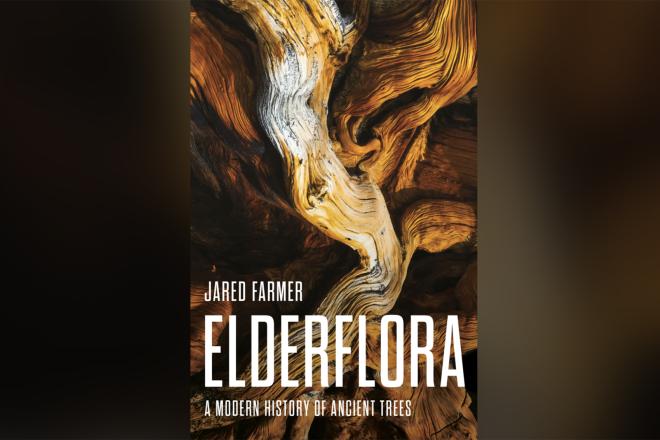

Humans have a long history of venerating ancient trees. That reverence and care taking took a modern turn in the 18th century, when naturalists embarked on a quest to locate and date the oldest living things on Earth, as historian Jared Farmer narrates in “Elderflora: A Modern History of Ancient Trees.” His book, which hits shelves this week, takes readers from Lebanon to New Zealand to California, looking at the complex history of the world’s oldest trees and how they can help us address the climate crisis.

The official book launch will be held at Penn’s Morris Arboretum Oct. 23, as part of Alumni Weekend.

Penn Today spoke to Farmer about the book, why humans have no trouble looking at the ancient past but can’t seem to envision the deep future and what trees can teach us.

“Ancient trees are bridges between short time and deep time, between lived human time and abstract geological time,” Farmer says. “We have to create emotive connections to the far future in order to work together on climate now.”

Q: What inspired you to tackle this topic?

First, I wanted to write a book about climate change. Second, I wanted to write about long-term thinking, another great challenge of our time, and closely related to the first. We’ve already changed the climate going forward centuries, maybe millennia, yet we humans are surprisingly bad at thinking about the long future. However, we’re really quite good at thinking about the long past. It’s one of the notable characteristics of humans: We care about our ancestors; we care about ancient civilizations; we visit cemeteries; we observe days of the dead; we’re constantly referencing people and events that happened hundreds or thousands of years ago.

Of all the ways I could have grounded those two themes—climate and time—I kept coming back to trees, tree-rings, and tree-ring science. Previously, I’d written a history of California with trees—it’s called ‘Trees in Paradise’—but this time I decided to write a book about trees. To my surprise, I became a serious botany nerd and major tree-hugger, a term I no longer regard as a pejorative at all.

For several reasons, trees are ideal for long-term climate thinking. Specimens of certain species can live for thousands of years. The cambium layers inside their wood contains data about past climates. At the population level, trees affect the water cycle and the carbon cycle. And, of course, a changing climate affects forests. Moreover, people have cared about—and cared for—ancient trees since ancient times. There’s a deep and powerful history here. Unlike the deep time of geology, which is all intellectual, the deep time of botany has emotional content. Much of my book concerns long-term relationships between people and individual trees.

So, I go as local as possible and then go as global as possible. Trees are hyperlocal. They cannot move. Their commitment to place is absolute. But they’re also connected to a dynamic planet that is constantly changing and changing faster now because of human influence. I came up with this notion, also an ambition, to write a ‘place-based planetary history.’

Q: Why is it important to look at the topic right now?

There’s been an incredible series of tree-themed books in the last decade. There’s the oeuvre of Peter Wohlleben, the German forester who’s now an international phenomenon. There’s Richard Powers, whose novel ‘The Overstory’ won a Pulitzer. Before him, Pulitzer-winner Annie Proulx wrote ‘Barkskins.’ The forest ecologist Suzanne Simard has a best-selling memoir, ‘Finding the Mother Tree.’ I could go on.

As for why this is happening, I think it’s due in part to the resurgence of the field of plant communication, especially the ‘wood wide web,’ the way that trees are connected to other plants through their roots with the assistance of fungi. The technical term is mycorrhizal network.

There are cultural and political dimensions to this new interest in arboreal science. ‘Mother tree’ is a metaphor for connectivity based on mutualism and care. This idea is very attractive in our current moment of miscommunication, disinformation, animosity, distrust, and political breakdown—basically everything we’ve seen since the advent of social media, as magnified by politicians in the United States and elsewhere.

People are just so angry all the time and distrustful of others, despite being ever more connected. So, this notion that there are beings out there who have a wholly different model of sharing and cooperating is inspiring. Now, you don’t want to anthropomorphize trees too much, but frankly some amount of personification is unavoidable, and I’m okay with that. There’s a venerable history of thinking of trees as person-like beings. In the end, I celebrate that tradition rather than denigrate it.

So, that partially explains readerly interest in woody plants. But there’s also a real crisis right now for forests and trees, especially old trees, and most especially big old trees, whose climate of establishment is now long gone. Anyone who follows the news has seen stories about climate-induced mass mortalities and diebacks of ancient sequoias, ancient olives, ancient kauris, and other long-lived species.

Q: The book is interdisciplinary in an unusual way. It has a lot of ethics, tree-ring science, philosophy, cultural history, and even religion in it. How did that come to be?

I don’t think you can solve the problem of long-term climate thinking without spirituality and religion, or at least by finding common ground with people who use the emotive power of religion to do their own kind of long-term thinking.

Trees are such important cultural symbols, including religious symbols, and now they’re incredibly important data producers and data containers, thanks to tree-ring science. There’s a way you can get at science from religion, and vice versa. When we talk about old trees, it’s often as sacred beings, as sanctified plants. Often they grow in temple compounds or shrines or church yards. But they can also be sacralized through science and set apart by the state. Here in the U.S., there’s Sequoia National Park and the Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest. These are essentially secular sacred groves. They don’t have priests, but they have rangers who are called to protect these trees that most visitors would describe as sacred.

Somewhat like ancient scriptures, ancient trees are bridges between short time and deep time, between lived human time and abstract geological time. There’s a lot of geology we can relate to emotionally, if we include trees, and there’s time for a shared geologic future with trees. We have to create emotive connections to the far future in order to work together on climate now. As person-like plants, as ethical beings, ancient trees help get us there.

Trees figured out so long ago how best to live on Earth. They’re solar-powered, vegetarian, and committed to their locale. There’s something deeply inspiring and deeply Earth-appropriate about that way of living. There’s a reason why woody plants have been going strong for hundreds of millions of years. But there’s no reason to think our species can’t have at least a few million more years in its future, if we learn to live appropriately alongside life-forms that preceded us and will surely outlast us.

Q: What do you hope people take away from this book?

First would be an appreciation for the depth of history of people caring for old trees. There’s such a long record of care taking, of veneration, of stewardship.

I also hope readers come away with an appreciation for tree-ring science. It has immediate applications to the humanities and social sciences. It’s not abstract. These trees generate and store proxy data about climate, weather events, and natural disasters—planetary to regional to local events that can be tied to calendrical dates that can be tied to historical chronicles. Tree-rings really enrich our understanding of the human past.

I also want readers to get a sense of urgency that this is a time of crisis for megaflora. There’s no way around that. For a lot of the biggest, oldest trees, this is the time of twilight. It’s very melancholy. I want to suggest to readers that we are so lucky to know these trees, to know where they are, and to have opportunities to live with them or visit them. No one should take that for granted.

Lastly and maybe most important to me is the sense that trees help us think about longer units of time, backward and also forward. There are few human faculties we need to develop more than hindsight and foresight, preferably by combining them. Having written this book, I might even say there’s nothing better than hugging a tree for nurturing habits of long-term thinking

Q: Do you have a favorite tree?

I do have special feelings about Great Basin bristlecone pine, since I’m from the Great Basin. Those are trees I visited as a child with my father, and the mountainous environment they grow in makes me feel deeply at home even though the area seems inhospitable.

But the more I read about ginkgo, the more amazing I find the species. Its lineage goes back to the Jurassic. Ginkgoes survived multiple mass extinction events and persisted through ice-free periods and ice ages. They’d almost gone extinct when humans came on the scene. So, their modern history is one you can feel good about. As of the 18th century, ginkgoes were restricted to East Asia. Now they’re everywhere in the temperate zone. Ginkgo is a common street tree in Philadelphia, which frankly seems more inhospitable to me at times than Great Basin mountains. You see them growing in tiny plots of soil that are surely contaminated. Each one has multiple wounds healed over. Today, because of online delivery, they get hit by trucks all the time. In the 20th century, these trees managed to grow upward and claim canopy space above the rowhouses, despite the city’s terrible air quality. When I walk to and from Penn’s campus, and see these scraggly ginkgoes miraculously still existing, I feel the depth of tree time.

Of course, there’s the smell of the fallen fruit in fall. But when you think about the journey of this species across the vastness of time and space to get to this place, right here in Philadelphia, suddenly that sweet-rotten smell doesn’t seem so bad. Sure, it stinks, but it’s also the atmosphere of deep-time persistence. There has been a very long past for people and trees, and we should keep the relationship going, as long as humanly possible.