Leveraging ecosystems-based solutions: insights from a workshop of the Convention on Biological Diversity

Beach dunes, mangroves, and urban forests are beautiful landscapes, but they also exemplify the essential role of ecosystems in adaptation strategies and reducing disaster-related risk under a changing climate. But how can we effectively devise and manage ecosystem-based solutions to protect people and nature?

By Xime Trujillo and Carolina Angel Botero

Beach dunes, mangroves, and urban forests are beautiful landscapes, but they also exemplify the essential role of ecosystems in adaptation strategies and reducing disaster-related risk under a changing climate. But how can we effectively devise and manage ecosystem-based solutions to protect people and nature? This question was first formally addressed in 2019 when the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) published the Voluntary Guidelines for Designing and Effectively Implementing Ecosystem-based Approaches to Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction. These serve as a roadmap for integrating biodiversity conservation into climate action. Fast forward to May 2025, representatives from academia, government, non-governmental organizations, community groups, and policymakers gathered at the United Nations Environment Program-World Conservation Monitoring Center in Cambridge, England, both in person and online for a hybrid workshop to develop and provide input on a supplement aimed at enhancing the guidelines with an updated guide to tools and best practices for implementing them.

In this article, two workshop participants representing the University of Pennsylvania share their insights on biodiversity conservation, its connection to climate change, and their takeaways from the workshop.

Carolina Angel Botero, postdoctoral fellow, Center for Latin American and Latinx Studies

I examine the relationship between law and nature, employing an interdisciplinary approach that integrates anthropology and law. My interest in this topic stems from a desire to explore how knowledge about nature in legal settings can contribute to reconciling climate justice and climate advocacy with current discussions on biodiversity. I am currently involved in studying judicial decisions regarding the rights of nature in Latin America.

Challenging conventional mindsets

The CBD workshop began with an inspiring moment from a participant, who shared their journey of bridging the gap between the climate (UNFCCC) and biodiversity (CBD) conventions. Addressing this gap set a reflective tone and led to a pivotal question that resonated throughout the gathering: What does it mean to take Mother Earth-centric actions?

Tristan Tyrell, program management officer of the Science, Policy, and Governance Unit at the CBD, urged attendees to shift from viewing nature merely as a source of ecosystem services to recognizing that humanity is an essential part of the natural world. This change in perspective sparked a deeper dialogue about the meaning of a Mother Earth-centric vision and its relevance to the challenges of climate change and biodiversity. It encouraged participants to rethink the long-held divide between people and their environment, but also found resistance among those who have long worked on the climate agenda, as such concepts held little resonance.

The discussions explored Ecosystem-based Approaches (EbA) and Ecosystem-based Disaster Risk Reduction (Eco-DRR). However, since the publication of the voluntary guidelines six years ago, there have been substantial developments in international policy and scientific understanding that the review of the Supplement needs to address. For instance, Nature-based Solutions (NbS)—a term officially adopted by the CBD in the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), approved in 2022 during the United Nations Biodiversity Conference in Montreal, frames the discussion around leveraging natural processes to solve problems produced by climate change and biodiversity loss.

We also engaged in a thoughtful discussion regarding the complex relationship between mitigation and adaptation strategies in environmental policy. As was noted by some of the attendees, it is puzzling to treat mitigation as a supplement to adaptation. The two approaches come from different scientific foundations and aim to tackle distinct issues; their methods can vary significantly and are not always compatible. A tension became evident: Although local needs and participatory methods typically drive adaptation efforts, mitigation strategies frequently adopt a top-down approach, leaving little room for co-design with communities. For instance, protecting ecosystems such as mangroves can provide local communities with some carbon benefits, but on a much smaller scale compared to other carbon-saving measures, like conserving vast Canadian forests. This divergence highlights the need for distinct carbon accounting practices to support mitigation efforts, while acknowledging that adaptation must be more people-centric, actively engaging local communities to understand their unique needs and perspectives.

Financing biodiversity conservation was also part of the discussion. Some key questions were: What is the purpose of finance, and who truly benefits? We examined the complexities of financial mechanisms, highlighting emerging trends such as carbon credits. Concerns about decision-making processes and the flow of financial resources were central to the conversation. This naturally led to the idea of biocredits, questions about the market's size, and governance structures. Voices from the group called for a more equitable distribution of resources, advocating for direct financial pathways that support local initiatives and communities.

In the closing moments of the workshop, participants delved into a critical question: What tools and practices can effectively expand NbS and EbA? Ensuing conversation highlighted the importance of prioritizing inclusive design, establishing clear governance structures, and integrating traditional and local knowledge systems into future initiatives. This focus on inclusive governance is not just a strategy but a call to action that encourages and involves everyone in the process of change.

Xime Trujillo, Senior Research Coordinator, Environmental Innovations Initiative

Urban rivers sparked my connection with biodiversity. Urbanization often alters streams, and runoff from impervious surfaces can carry hazardous dissolved and suspended materials that negatively affect water quality. Lower water quality, in turn, disrupts ecological cycles and poses threats to public health. Under a changing climate, rising temperatures and shifts in rainfall patterns lead to heavier downpours and prolonged droughts that further impact urban aquatic systems.

During the workshop, I found it enlightening to learn how halting biodiversity loss can serve as an effective principle for creating sustainable solutions across sectors, including water and health. In addition to the principles and safeguards reviewed, this was also an opportunity to get more familiar with the tools made available by the CBD’s Guidelines and Supplement to bring these solutions to reality. It was positively overwhelming to see such a wide array of toolkits, best practices, and real-world examples. Here are my five lessons learned.

Five key lessons

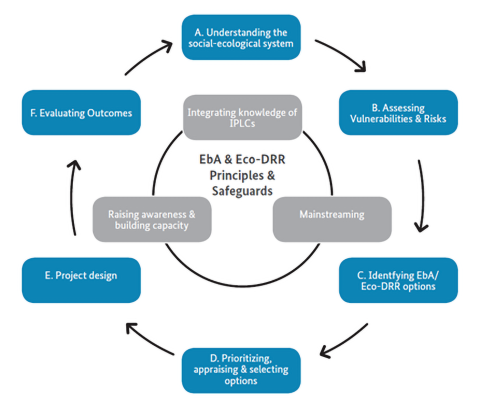

1. Good intentions, bad outcomes: The stepwise approach to design and implement effective solutions described in the guidelines is based on three principles: (1) Integrating knowledge of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLC), (2) raising public awareness by communicating the benefits of interventions across sectors, and (3) mainstreaming or integrating approaches into climate mitigation, adaptation, and disaster-preparedness plans. These principles are cornerstones for any EbA or Eco-DRR solution. For instance, the principle of mainstreaming helps to identify tradeoffs so that carbon, climate, and disaster risk projects do not lead to bad outcomes, including the spread of invasive species, loss of native species, and overall habitat degradation, and, as a consequence, missed mitigation and adaptation opportunities.

2. Iterative process: Bearing the principles in mind, the iterative nature of the stepwise approach included in the guidelines underpins the success of projects over time. For example, an analysis of peatland restoration projects in Ireland showed how rehabilitation led ecosystems back to Net Zero. However, the study also emphasized the relevance of long-term monitoring data to evaluate the restoration outcomes and assess the peatlands’ ability to remain sinks rather than sources of greenhouse gas emissions.

3. The first step is the hardest: Assessing climate risk is a complex but necessary task to identify effective measures among many potential solutions. However, the Guidelines and the Supplement aim to address economic and ecological vulnerabilities and risks in their assessment.

4. One size doesn’t fit all: The Supplement highlights the importance of “point solutions” or designs that are fit for specific purposes. Understanding the local socio-ecological system is key to devising solutions, regardless of scale and reproducibility. It also reiterates the need for solutions aligned with existing global, national, and local policies and regulations. Consequently, the Supplement underscores the relevance of adaptive toolkits or roadmaps to enable action.

5. Breaking down silos: Coordinating actions across sectors is feasible and essential for reforming the relationship between economy and nature. To enhance this point, the supplement features the Nexus Assessment Report, one of the latest publications of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). The Nexus report examines the interlinkages between biodiversity, water, food, and health in the context of climate change, emphasizing tradeoffs and compounding effects that result from addressing only one of these elements. The previous report is only one among various relevant resources included in the Supplement aiming to offer options to restore nature while maximizing the co-benefits of halting biodiversity loss.

Two perspectives, one takeaway

Drawing on diverse expertise and experiences, we both highlight the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in addressing climate impacts with solutions grounded in the resilience of ecosystems. We emphasize that achieving meaningful adaptation and disaster risk reduction strategies requires understanding both ecosystem dynamics and the legal frameworks that govern our interactions with nature. Our insights reflect a growing recognition that a holistic approach—one that marries ecological, legal, and social perspectives—is essential for fostering resilience and conserving biodiversity in communities affected by climate change.